It is estimated that more than 80 percent of new products fail, a phenomenon that’s experienced across the board by start-ups to large companies and organisations. That’s a staggering amount if you consider the time and cost involved.

But why? There are several main reasons.

If a product doesn’t solve a market problem or addresses its need, it becomes redundant fast.

This is arguably the main one reason why new products fail; there is no market need for them.

A product doesn’t come into existence overnight. It requires conceptualising, planning and execution. However, teams commonly are stuck in a perpetual planning loop.

The focus on setting and ironing out all the details in terms of what needs to be done often eats into the important time needed for actual work to begin.

This is usually the result of spending too much on the desire to build a perfect product from the start. The repeated process of refining after refining leads to an finished product missing the pivotal launch window. The market might have moved on or their needs were met by a faster, competitor product, capitalising on the first mover’s advantage.

When the time to market is slow, a product can be of no use because, among other things, changes in demand happens. As a result, the golden opportunity to meet (current) needs is missed.

Why this happens could be boiled down to various reasons such as non or miscommunication and even unnecessary last-minute tweaks made on the product.

A contributing factor to why a new product fails can be attributed to having a mindset vulnerable against the fear to experiment and fail. Despite many success stories of mistakes and failures that have done a turnaround, many are still afraid to fail.

Perhaps, the stigma often attached to failures have discouraged people from experimenting. The truth is, if a product maker does not experiment and is not brave enough to fail, it’ll be hard for them to figure out what the market actually needs.

Many non-Agile organisations may suggest a culture of experimentation, but failure is still looked down upon.

This philosophical dissonance makes it difficult for teams to reconcile the desire to experiment and learn from failure when there is a fear of being singled out, or worse, having the project completely scrapped and jobs threatened.

While the culture of experimentation is much-welcomed, equally important is the ability to recover fast from setbacks.

The team in a company or organisation needs to be able to pivot and return on track swiftly when a flaw is discovered at any stage, including after a market level failure. This will test a teams’ mettle on many levels, especially in solid collaborative culture.

This is an essential capability all Agile teams must possess.

So, with the high percentage of new products failure, what can be done to mitigate the risks involved?

01. No market need

If a product doesn’t solve a market problem or addresses its need, it becomes redundant fast.

This is arguably the main one reason why new products fail; there is no market need for them.

02. Too much time spent on planning and focusing on building the perfect product

A product doesn’t come into existence overnight. It requires conceptualising, planning and execution. However, teams commonly are stuck in a perpetual planning loop.

The focus on setting and ironing out all the details in terms of what needs to be done often eats into the important time needed for actual work to begin.

This is usually the result of spending too much on the desire to build a perfect product from the start. The repeated process of refining after refining leads to an finished product missing the pivotal launch window. The market might have moved on or their needs were met by a faster, competitor product, capitalising on the first mover’s advantage.

03. Time to market is slow

When the time to market is slow, a product can be of no use because, among other things, changes in demand happens. As a result, the golden opportunity to meet (current) needs is missed.

Why this happens could be boiled down to various reasons such as non or miscommunication and even unnecessary last-minute tweaks made on the product.

04. Afraid to fail

A contributing factor to why a new product fails can be attributed to having a mindset vulnerable against the fear to experiment and fail. Despite many success stories of mistakes and failures that have done a turnaround, many are still afraid to fail.

Perhaps, the stigma often attached to failures have discouraged people from experimenting. The truth is, if a product maker does not experiment and is not brave enough to fail, it’ll be hard for them to figure out what the market actually needs.

Many non-Agile organisations may suggest a culture of experimentation, but failure is still looked down upon.

This philosophical dissonance makes it difficult for teams to reconcile the desire to experiment and learn from failure when there is a fear of being singled out, or worse, having the project completely scrapped and jobs threatened.

05. Team is unable to recover fast

While the culture of experimentation is much-welcomed, equally important is the ability to recover fast from setbacks.

The team in a company or organisation needs to be able to pivot and return on track swiftly when a flaw is discovered at any stage, including after a market level failure. This will test a teams’ mettle on many levels, especially in solid collaborative culture.

This is an essential capability all Agile teams must possess.

So, with the high percentage of new products failure, what can be done to mitigate the risks involved?

The Design Sprint methodology

The design sprint is a five-day process for answering critical business questions through design, prototyping, and testing ideas with customers. – Jake Knapp (Author, Inventor of “Design Sprint”)

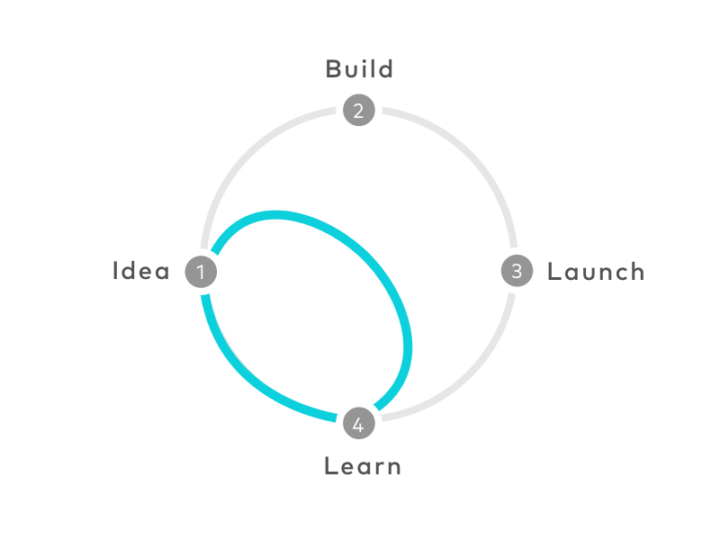

Design Sprint is essentially a framework that helps to answer critical business decisions fast. It helps define a need for a product and build the right one to solve a market problem.

Design Sprint facilitates the quick construction of a prototype or mock-up that highlights its key features and functions that can be tested against a customer’s needs. This enables honest feedback early so that changes can be made fast.

It also promotes collective intelligence and contributions from cross-functional teams for a fruitful collaborative effort. It does this by combining Design Thinking and Agile principles framework.

The Design Sprint methodology’s success is evident, and a noteworthy example is KLM Royal Dutch Airlines’ X-Gates.

KLM is the world’s oldest commercial airline that has managed to remain competitive and remain at the forefront of innovation and customer-centricity; no easy feat considering the tight regulations the industry operates under.

As mentioned, a Design Sprint enables the quick design and build of a prototype that can be tested against customers’ needs for real-time feedback.

With Schiphol being one of the busiest airports in Europe as its premise, KLM set out to improve its customers’ experience by inviting them to provide feedback or ideas, which were then quickly transformed into prototypes and implemented on the spot with room for changes (catering to the ongoing feedback).

Those tests were able to immediately identify customers’ pain points. The airline did all these without disrupting its airport operations.

This collaborative process was called X-Gates. Since its inception, it has become a method adopted by other airlines to improve how they interact and service their customers.

Design + Sprint

But what is Design Sprint exactly? And where did it come from?

Design Sprint, a brainchild of Google Ventures (GV), is a five-day design process from concept to fruition. Google Ventures realised that start-ups, with their limited capital and resources, needed help identifying whether they were building the right products and fit for the market.

They came up with the Design Sprint framework to help companies mitigate risks early on and answer critical business decisions fast. It became a hit, and soon, companies and organisations of various sizes started to implement the methodology.

To understand what Design Sprint is, one should be acquainted with its two elements – Design and Sprint.

Design means a lot of things to different people, but in essence, it’s about designing a solution to solve a problem. Not just any problem, but the right problem.

Simple enough, but its most critical element, knowing “who” it’s being designed for, must always be in focus.

Knowing the “who” means understanding:

- the “what” – the needs and the actual problem that is to be solved,

- the “why” – the importance and value of the solution and

- the “how” – the process from concept to reality and how the solution will solve the problem and add value.

These form the core of design-thinking or design-led solutions.

In a nutshell, a sprint involves achieving optimal results in the shortest time possible with maximum effort. A parallel of sorts can be drawn to participants in athletic sprint events.

They’re not expected to run very far, but in the short distance that they do, they’re able to exact enough speed to get to the finish line with the intent of winning the race.

Design-thinking isn’t necessarily interested in winning any sort of race, but it is meant to help teams get the best results in the shortest time possible with maximum effort.

The sprint element is in the form of the timeboxed five-day duration that a Design Sprint process sticks to. In that time, the team is expected to focus solely on the tasks defined for that sprint.

In business, usually, resources are limited. Time and money, therefore, need to be spent wisely.

In a Design Sprint, this is typically kept in mind as the most essential features are always prioritised over the more aesthetic ones.

Resources should be spent on solving the right problems and ideas first. Once you cross that finish line, then comes time to iterate and introduce the nice-to-have features.

The 5-day design sprint process

The aim is not to build a perfect product, which can result in time and money wasted with the added effect of the product either never releasing or releasing so slowly it is no longer market-relevant.

In a Design Sprint, the goal is to build a prototype that can be tested by real users, who will supply valuable feedback on further improvements that need to be made in real-time.

Day 1 (Understand)

Understanding the customer and their needs is what the first day is spent on.

Teams developed an awareness of the business landscape by performing a competitor review. The first day sees the problem identified, and a strategy formulated.

Day 2 (Diverge)

The focus on day two is on brainstorming and developing a range of solutions that will best address the problem. At this stage, it is the quantity instead of the quality of the solutions that matters. There are no bad ideas, however improbable, in the Diverge step of a Design Sprint.

The point is to think as much as possible and as far out of the box as you can to come up with potentially creative solutions that can be pared down and refined later on.

Day 3 (Converge/Decide)

Day three is when teams will come together and decide on the best solution that will solve the problem. This is to facilitate the next step, which is to build a prototype.

Day 4 (Prototype)

Building the prototype takes precedence at this stage. High on the priority list are building and testing the usability of the product’s critical functions and features. Aesthetic and other “add-ons” should not be a concern here.

Day 5 (Validate)

Day five is when the prototype is presented to real users and the customer. From the reactions, feedback is gathered to make improvements to the product.

This entire process utilises the design-thinking framework, better known as the 4D Framework of Discover, Define, Develop, and Deliver.

When is Design Sprint used?

When launching anew product or service, a Design Sprint is extremely useful. It is also used where the goal is to extend a user experience to a new platform. For example, converting an offline experience into online or integrating the two.

This can be tied to creating a new customer experience.

Other common uses include improving UX/UI design and adding new features and functionality to a digital product. The purpose and goals are varied, but organisations and companies often use them to create new consumer-driven products or disrupt the market.

An example where Design Sprint has helped an organisation create a product for a particular group on a massive scale is the ShareTheMeal app. According to its founder, Sebastian Stricker, the app was to aid the United Nations World Food Programme’s initiative to end world hunger using disruptive technologies.

It was based on a simple idea to create a transparent solution where issues like the complications of hidden fees and others associated with donating to charities are reduced. The app was and still is a success, with over 90 million shared meals to date.

Case Study: Design Sprint in Wealth Management

The client is a Global Wealth Management company based in the United Kingdom with a regional office in Hong Kong. The focus was to create an account opening experience that was easy and unique in an app.

Before engaging a Design Sprint expert, discussions had been ongoing for eight months. Upon engagement, the Design Sprint team set on their task. A team comprising the Chief Marketing Officer, Head of Operations, Product Owner, Scrum Master, UX/UI Designer and two Developers were assembled.

The objectives were first laid out, and these include identifying what the product is going to be, the targeted customers and how the product can bring value to them, and other insights.

The task was to create something quick with insights to be tested against real users for initial reactions.

The 5-day Design Sprint process was employed.

Day One

The Sprint Goal was identified on Day One, and this was to create a quality investment platform for the targeted market to grow and manage their wealth. This acted as a guide or compass for the team, so no one loses track of the goal.

Identifying the right problems to solve based on gathered feedback on current customer issues was also a vital component of the day.

Defining the product vision means what the product will look like, its purpose, how it will solve the problem, and bring value to the customer.

Assumptions about the product were listed. Some included the team members’ own perceptions of the product including the belief that customers would pay for it.

At the end of the 5-day sprint, these assumptions were either going to be validated or disproved.

Day Two

Day Two centered around the theme of divergence, where ideas were discussed, and brainstorming sessions were conducted.

Each team member would consider the other’s idea and figure out how it could be incorporated into their own.

This collective intelligence process generates as many solutions or ideas as possible, focusing on quantity, not quality.

At the end of the day, the team made detailed sketches of their ideas to allow everyone to better visualise the solution or product.

Day Three

A decision was made on Day Three.

This is based on a collaborative vote by everyone in the team. Potential issues were discussed, along with the chosen solution.

The key component is the collective decision, as this is the purpose of having cross-functional team members. The solution (which was collectively voted for) was then transformed into a storyboard that serves as a blueprint for the product prototype.

This storyboard (kept within 15 frames) serves as the start and endpoint of the targeted customer’s journey. The storyboard is there to validate only the most critical of features.

Day Four

Today, the blueprint was turned into reality; a working prototype of the end-product. The focus is on creating an app that would facilitate a unique and easy account opening.

Day Five

Today’s focus was on testing the prototype on real customers. Members of the targeted segment were invited on-site to get their reactions.

Two cameras were set up; one focusing on the app and the other on the customer, the latter to gain valuable insights such as body language and other reactions.

Two team members were tasked with interviewing the customers based on their experience while the other team members were placed in a room where a live-feed of the test sessions was streamed so that they could observe and take notes.

The team was amazed at the process because it allowed them to receive real-time feedback swiftly on a matter that had been caught up in a discussion loop for eight months.

At the end of the 5-day sprint, the company had:

- A product vision identifying the purpose of the product

- Identified the targeted customers

- Identified the value of the product and pain point, which is account opening

- Defined the part of the customer journey to focuse on

- A working prototype

- Gained valuable insights from real-time testing with real customers

They finally had something concrete to work on.

Design Sprint Key Takeaways

According to Google Ventures, the 5-day Design Sprint gives companies a means to fast-forward into the future to see their finished product and obtain customer feedback via their reactions before making any expensive commitments.

Whether your product has a high business value or a small one, it doesn’t impact the importance of a Design Sprint. A Design Sprint’s main purpose is to identify needs and determine if the product you are building is the right one.

In a nutshell it:

- Helps to identify the right Product/Solution for the right problem

- Helps to build a working prototype fast

- Facilitates the testing of the prototype with real customers

- Enables collective intelligence, which validates or improves on existing ideas

- Uses Design Thinking and Agile principles

Today, changes are happening at a seemingly breakneck pace. To keep up or stay ahead not only does it require speed but, more importantly, knowing when to conserve and expand energy much like an athlete in a century spring.

And the best way to do that in business is by holding a 5-day Design Sprint. The time spent may be minimal, but the results are anything but.

Interested in having a Design Sprint workshop?

The Design Sprint course will give you and your team the toolkit to apply to solving different kinds of complex problems.